Audiences watching Polar Express, the first CGI musical fantasy reported a gamut of conflicting emotions. Somewhere between “Dang, this is some futuristic animation” to “Stop! Get me off this train” is where they experienced Uncanny Valley. IIITH student Medha Sharma’s research paper deep-dived into this strange phenomenon.

“What do you do when your internet is on the fritz? Do I talk to a digital avatar, AI or an actual person?” asks Medha Sharma who is currently pursuing her masters at the University of Colorado, Boulder. We are moving to a space where digital avatars are everywhere, as professional assistants or as your favorite gaming character or action hero. However, it is noted that as digital avatars increasingly approach human-like physical resemblance, there comes a point when viewers report sensations of unease or eeriness; a phenomenon now referred to as the Uncanny Valley effect (UVE).

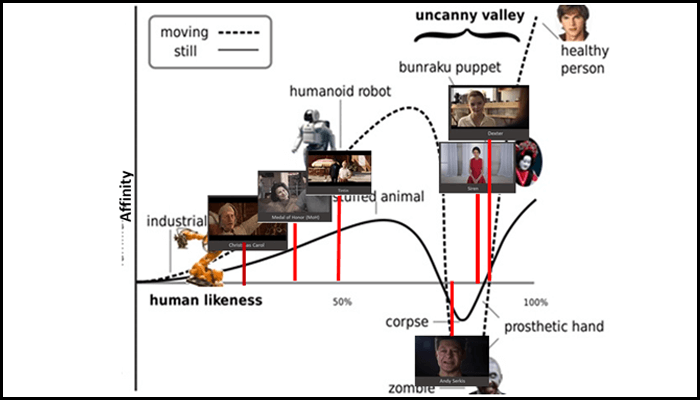

“The concept propounds that as animated avatars or robots approach 80% resemblance to humans, there is a dip, described as the valley. We get a very weird feeling that shouts “I don’t really like what I am looking at”, explains Medha. The researcher was a 4th-year B. Tech student at IIITH’s Cognitive sciences lab under Prof. Kavita Vemuri, when she published her first paper on the phenomenon, as part of her honors work.

Genesis of the UVE theory

The UVE hypothesis was initially proposed by Masahiro Mori and applied to robots in the 1970s. He used the phrase bukimi no tani that translates to creepy, uneasy or strangely repulsive. Recent studies also encompass the physical and facial features of digital avatars and prefer to use the term “eerie” (strange, weird and fear-inspiring).

Three experiments into the Uncanny Valley

Medha’s interest in the subject was piqued when a visiting professor to IIITH spoke about it. “It was interesting to investigate the point where we might not be comfortable with Augmented Reality that we are so devoted to creating”, she says. Over a period of one and a half years, her mentor Prof. Kavita Vemuri guided her in the design of three experiments that would investigate three specific research areas in UVE and realism. The study spanned physical appearance, gender of robots/digital agents, kinematics, emotions and human interactions and acceptance of digital avatars.

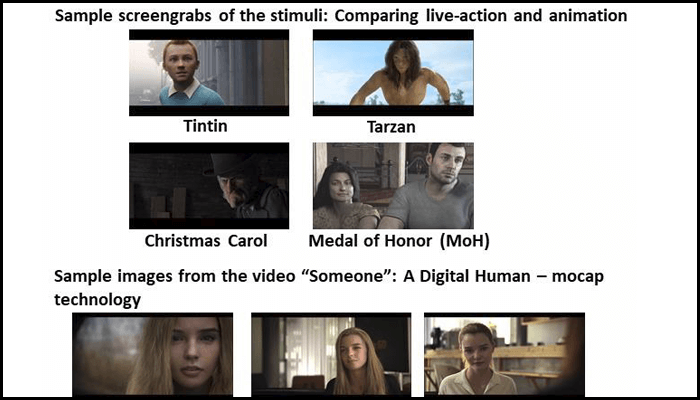

First experiment on Deja view of eeriness

“For the first experiment, we examined perceptive evaluation of actors in clips from animation films versus the live-action version of the same movie”, reports Medha. The Stimulus presented for the cohort study on 22 participants (male and female, age group 18-22) were clips from Tintin (animation-2011, live-action-1961), The Christmas Carol (animation–2009, live-action-2004) and Tarzan (animated–2013; live-action-2016). “We juxtaposed similar scenes and did eye tracking to understand what people are looking at and which were the points in the animated avatar that they found eerie”. In addition, clips from the computer game Medal of Honour with CGI avatars was included since online reviewers had labelled it as creepy.

No significant differences were reported by the participants who were computer science students, knowledgeable about motion capture (mocap) technique and CGI. This conclusion brought them to the second experiment.

Second experiment on technical awareness and the Digital Human

What if the avatars were introduced to viewers who were not exposed to it before? Would they find it eerie or just be awed by it?” Thus for the second experiment, the cohort were maintenance staff (male, ages 18-30 years) who were not computer-literate against a sample of B. Tech students. Here, the research question was the role of technical awareness of CGI and mocap on the sensation of eeriness.

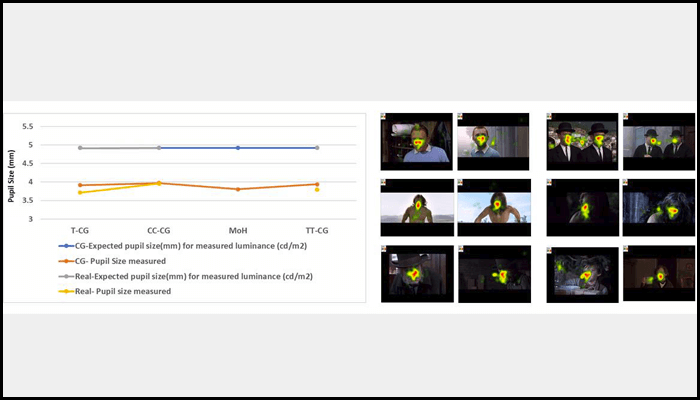

Participants watched a short video from Dexter Studios and answered unstructured questions in their mother tongue (Telugu or Hindi). The video clips of the highly realistic digital avatars (Dexter and Siren) were measured for recognition ability, the extent of eeriness and specific physical features that they identified as unreal. The fixation area and pupil size variation were recorded using an eye tracker and analyzed to infer attention to the body, face, and emotional response, respectively.

Third experiment on Role Acceptance of the Digital Avatar

The third experiment looked at acceptance in roles requiring human skill, empathy and cognitive ability. “The basic idea was to understand how comfortable you would be to accept a robot working with you as a colleague, friend or assistant”, says Medha. If they are our colleagues, how much intelligence do we attribute to them? Do parents think it’s safe for their child to have a robot as a playmate or nanny?

Based on existing studies, the hypothesis was that acceptance in human-like interactions and decision-making roles would increase as human-likeness increases. Six computer-generated animation clips with increasing realistic rendering were shown for 30-40 seconds, to 65 participants (both sexes, B. Tech students in computer graphics and AI) and a comprehensive 4-part questionnaire was administered.

What they discovered

Participants provided descriptive answers to questions that were designed to explore unconscious perceptions of facial and body features that identified the character as a CGI /animated. For Tintin and the Christmas Carol, the significant markers that identified them as CGI was the unnaturally smooth skin texture and color, eyes, nose, facial expression and structure, body build and clothes. For Tarzan and Medal of Honor, the hair form and movement were the first clues to give them away as computer-generated.

The characters were rated on a semantic differential multidimensional scale of frightening-reassuring, spine tingling-uninspiring, thrilling-boring, uncanny-bland and supernatural-ordinary. CC, MoH and Andy (all-male actors) scored higher on the eeriness quotient and pegged a lower humanness index. Tintin being a familiar comic character rated lower on the eeriness quotient even though anthropomorphism (humanness) was higher. Interestingly, Dexter and Siren are considered less eerie though high on the humanness index.

Acceptance of the digital avatars

“Everyone had grown used to giving orders to the pleasant-voiced feminine robots.” ‒ Laura Lam, sci-fi thriller ‘Goldilocks’.

Data analysis indicates that humans are more willing to accept digital avatars as assistants to do laborious, controlled tasks and not so much in work that might require artistry, evaluation, moral judgement, decision making and diplomacy or as child caretakers. The animated agents’ lower acceptance as colleagues can be due to the perception of embodied virtual agents as a threat to livelihood. The sense of eeriness shows a sharp increase when the avatar is talking and dips for the smiling action, possibly due to cognitive dissonance when the avatar engages in humanlike movement (talking) or emotions (smiling).

“We examined if real-life social stereotypes and gender bias were transferred to high-fidelity avatars of Dexter, Siren and Andy. We saw that the female characters were considered less proficient in unskilled labor and military roles but higher as artists. For the software engineering job and artists, we saw that everyone was gender neutral”, observes Medha. The results also show that based on perceptions from physical attributes, the eeriness scores diverge from the theory as human-likeness increases. Realistic CGI and mocap (motion capture) technology could have helped cross the valley.

Re-charting the topography of Uncanny Valley

Recent innovations in humanoid robots from Boston Dynamics, Sophia , Neon (Samsung) and Uneeq (Amelia) have ignited fresh debate over the introduction of embodied virtual agents into living spaces and professions.

“Our study is the first step in our understanding of the multi-dimensional approach needed when applying the uncanny valley effect”, sums up Medha. “Our focus was more on the social and cognitive angle, on how people react to the technologies, examining our inhibitions and about accommodating them in our lives.

When there’s human interaction with digital avatars, it’s important to know where the lines are and where the minefields lie.” From our research we place the Dexter studio avatars to have crossed the valley and almost reaching human (plot below)

Kavita explains, the research on uncanny valley phenomenon was examined when avatars were being created for games, the discussions was on how ‘realistic’ should it be, and would player experience be better. The focus was on making them human-like, and when Prof James Foley ( a big thanks to him for initial pointers), of Georgia Tech during his talk mentioned the perception of eeriness I got interested. While most studies looked at visual descriptors, we explored the larger question – will humans accept them in co-existing roles. The research results in a paper (ACM THRI, https://doi.org/10.1145/3526026) which took me long (8 months) to write with data from three experiments and making the connections to social cognition.

The idea is not futuristic, there are a number of products already in the market. For example, a startup (Intellitar) way back in 2015 offered to create digital doppelgangers of those who have departed. It did not take off, as people felt it was eerie and psychologists raised concerns over its effect on mental health. Hence, it is important to explore not only the heights of technology but also its acceptance.